I continue to get questions about various events and individuals in the sporting community who have made an impact on sport and wanted to share the following.

Thanks to Doug and Diane Clement for sending this over and enjoy the read:

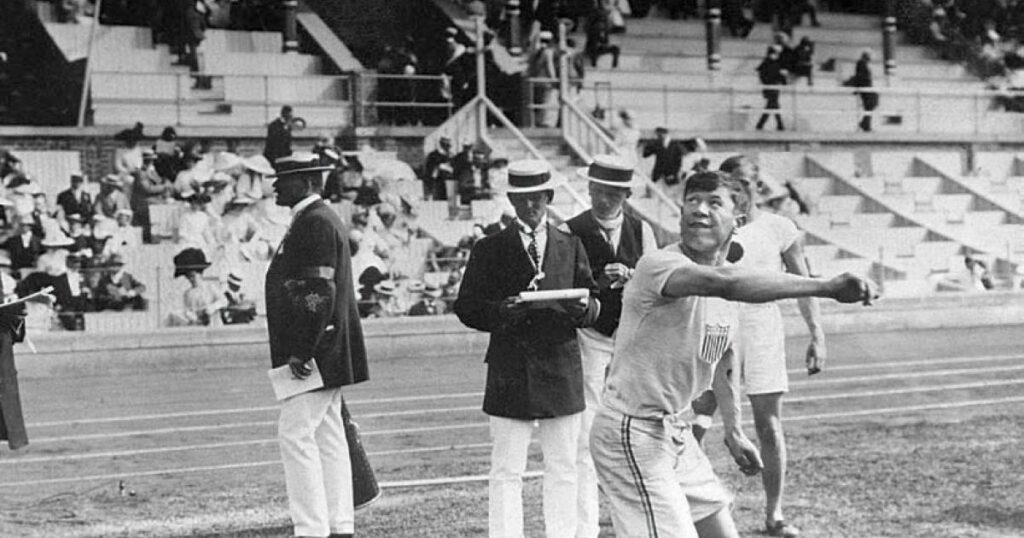

In 1950, the Associated Press named Jim Thorpe “Greatest Athlete of the Half-Century.”

The poll of nearly 400 sportswriters and broadcasters ranked him above such stars as Babe Ruth, Jack Dempsey and Joe Louis.

No one else sculpted so many contours of American sports history.

Thorpe had won two gold medals in track and field at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, twice earned all-American honors as a do-everything college football star, played six seasons of major league baseball and helped establish the National Football League.

He even barnstormed on the early pro basketball circuit.

Yet Thorpe’s story evokes a sense of loss. As David Maraniss artfully demonstrates in the biography “Path Lit by Lightning: The Life of Jim Thorpe,” Thorpe was both puffed and pilloried. The press crafted his image as both a noble Indian and a simple savage. Sports administrators stripped him of his gold medals for violating the dubious tenets of amateurism, and despite his status as a transcendent athlete and Native American hero, he struggled to find consistent, lucrative work. Maraniss states that he was a victim of the harmful myth “that the Great White Father knows best.”

A member of the Sac and Fox nation, Thorpe grew up in the Indian Territory of central Oklahoma and earned fame at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, a Pennsylvania institution that sought to “civilize”

Native Americans through regimentation, manual labor and cultural assimilation. Like many of his classmates, Thorpe both resented and appreciated Carlisle.

Like other aspects of American policy in the Progressive Era, it sought to uplift Indians, even as it treated them with racist contempt.

Thorpe vaulted to fame as the star of Carlisle’s football team, playing running back, defensive back, kicker and punter. In 1911, his squad raised the school’s profile by beating top college programs and winning the national championship. In 1912, Thorpe led a symbolically charged victory over Army (a team that included second-year cadet Dwight D. Eisenhower). In the words of Maraniss, Thorpe displayed “the uncommon multiplicity of his running skills — his change of pace, stop-and-go, swivel hip swing, straight-arm, and burning speed, all with the power of a wild horse pounding the Oklahoma prairie.”

Between these legendary seasons on the gridiron, Thorpe won both the decathlon and the pentathlon at the Olympic Games in Stockholm, a feat so remarkable that King Gustav V of Sweden purportedly greeted him, “You, sir, are the most wonderful athlete in the world.” While some press reports treated him as the Indian stereotype of a feral creature,

Thorpe also was hailed as an exemplar of American achievement — an irony, considering that the U.S. government did not recognize Native Americans as citizens.

When the Amateur Athletic Union stripped Thorpe of his gold medals in 1913, it ran along these historic patterns of condescension and exploitation. In his era, the lines between professional and amateur were fuzzy.

Carlisle football coach Pop Warner, for instance, dispensed cash to his athletes, including Thorpe. But when the press started reporting that Thorpe had spent two summers in North Carolina playing minor league baseball — a common practice for college athletes — it was treated like a scandal. Warner, along with Carlisle superintendent

Moses Friedman, disingenuously cast Thorpe as a simple, ignorant Indian boy who turned professional without their knowledge.

Maraniss is much more sympathetic to Thorpe. Throughout a book marked by deep research and expert context-setting, he sifts through the myths about Thorpe and Native Americans, depicting his subject as a proud, complicated man who sought to shape his own destiny, yet was bedeviled by larger forces of racism and hypocrisy.

An associate editor at The Washington Post, Maraniss owns a well-deserved reputation for crafting meticulous, sweeping narrative histories of American politics and culture, including works on sports. His book on football coach Vince Lombardi, “When Pride Still Mattered,” might be the best sports biography ever written.

If “Path Lit by Lightning” cannot reach that impossible standard, it is largely because Thorpe kept his thoughts and emotions to himself.

His stoic personality loaned him a shield from the pressures and prejudices that accompanied his unique celebrity, but he also played some role in his own struggles.

He let his first two marriages fail. He had distant relationships with his eight children.

He struggled with alcohol abuse. Maraniss pulls out the few shreds of evidence that reveal Thorpe’s unfiltered personality, but it is often difficult to see the man behind the mask.

Thorpe’s story reaches its dramatic climax during his glory years at Carlisle and in the Olympics, so the later chapters of his biography chronicle an ever-rambling life on sports teams of diminishing prestige; unsatisfying stints as a one-line actor or extra in Hollywood films; and short-lived gigs as a public speaker, traveling entertainer or saloon owner.

Yet by highlighting Thorpe’s perseverance, Maraniss paints a portrait with both heroic and tragic shadows. He writes, “Rarely demonstrative, more introvert than showman, lonelier than he ever showed the public, he endured nonetheless as the itinerant entertainer, the athlete, the Olympian, the Indian in constant motion, moving from one city to the next across America, fueled by a combination of willpower and often desperate financial need, searching for ways to adjust and survive.”

At the end, Maraniss tells the tale of Thorpe’s bones. They now lie under a shrine in the old coal country of the Pocono Mountains.

The small memorial park is in a town called Jim Thorpe, Pa. Despite his decades of constant travel with countless sports teams, Thorpe never set foot there.

Thorpe had asked to be buried near his Oklahoma birthplace, in the lands of his ancestors.

His widow instead profited by arranging for two municipalities to merge and rename themselves after the famous athlete.

In return, the town received Thorpe’s remains, along with unrealized promises of economic development.

In death as in life, then, Thorpe was a celebrated hero, but one commodified beyond his control and stripped of his authentic identity. “Path Lit by Lightning” tells his story with skill and integrity.

Aram Goudsouzian is the Bizot family professor of history at the University of Memphis.

His books include “King of the Court: Bill Russell and the Basketball Revolution.”

Path Lit by Lightning, The Life of Jim Thorpe

By David Maraniss Simon & Schuster. 672 pp. $32.50.

Advertise With Sportswave

About Sportswave

SICAMOUS HOUSEBOATS

Delta Islanders Jr. A Lacrosse

North Delta Business Association